A high schooler's guide to 'A review of mechanistic models of viral dynamics in bat reservoirs for zoonotic disease'

by Anecia Gentles

If my new paper made you feel like this…

Here’s a little explanation.

On mechanistic models…

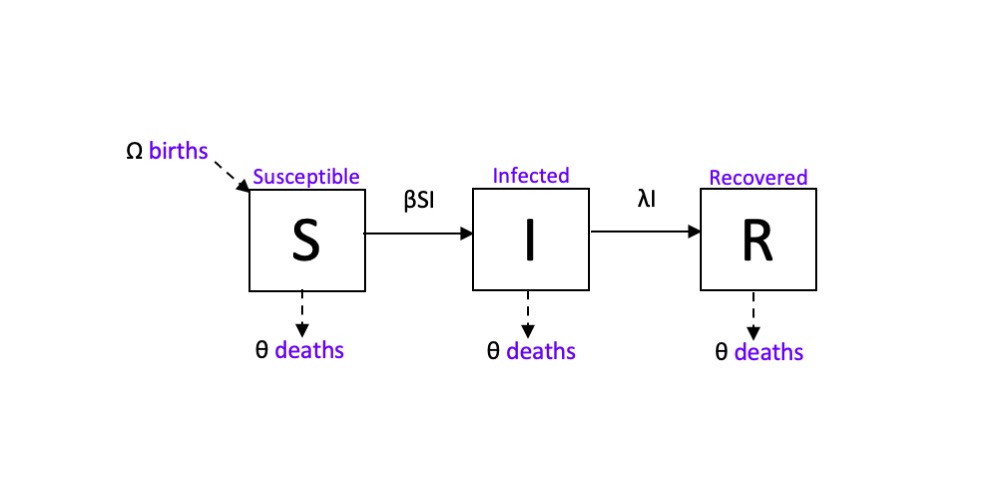

The magnitude of the SARS-CoV-2 (or COVID-19) pandemic has brought the work of medical professionals, epidemiologists and disease ecologists to the forefront of the world’s collective consciousness; and, for the first time in a while, everyone is asking how exactly did a bat virus become a very big human problem. As we learn more and more about how this virus spreads, epidemiologists continue to improve models of human to human transmission by building upon a framework called a compartmental or mechanistic model. Known as the SIR (Susceptible, Infected, Recovered) model, this mechanistic model of transmission tracks the progression of a pathogen within an individual (cell to cell), a population (host to host), or across metapopulations by categorizing each entity by their infection status at a given time. These statuses include, but aren’t limited to: Susceptible, Infected, and Recovered; and the sum of the individuals of each status is equal to N, the population. A system of calculus equations is used to describe an individual’s change in status over time. The equations are modified by parameters such as the transmission coefficient (β), the rate of recovery (λ), and processes such as the death (θ) and birth (Ω) rate.

On mechanistic models of bat-virus systems

Disease ecologists also use the SIR model to understand transmission dynamics in animal species. SARS-CoV- 2 is believed to have originated from a Betacoronavirus lineage circulating in Rhinolophus spp. horseshoe bats of South-Central China. Although bats are the reservoir hosts of an impressive number of potentially zoonotic viruses, very little is known about the transmission dynamics or mechanisms that allow virus to be maintained in bat populations. This is due in part to the difficulty of catching bats, detecting active infections, and determining age for long-term studies. In this paper, we’ve found that there are only 25 mechanistic transmission models of bat-borne viruses published in the scientific literature. Of these models, thirteen are theoretical – in which the parameters are “borrowed” from similar systems, and twelve are fitted to data, with parameters estimated from data collected in a field system. We focused the majority of our analysis on the data-fitted models.

Lyssaviruses

The available literature focuses on three lyssaviruses in several bat species: rabies virus (RABV) in North American big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus) and Peruvian vampire bats (Desmodus rotundus); European bat lyssavirus type 1 (EBLV-1) in four insectivorous bat species in Spain; and Lagos Bat Virus (LBV) in African straw-colored fruit bats (Eidolon helvum). Broadly, bat-lyssaviruses can be represented by an ‘SEIR’ model framework – in which ‘E’ stands for the ‘Exposed’ class. Generally, the RABV studies that we reviewed agree that bats will either die or seroconvert (test positive for RABV antibodies) after exposure to an infected individual, and repeated exposure may lead to immunity. These variations in response to exposure may play a large part in maintaining rabies virus in bat populations. Bats exposed or infected with EBLV-1 or LBV also show similar dynamics, though migratory behavior and co-roosting amongst the Spaniard bat species appears to play a role in maintaining EBLV-1, and African straw-colored fruit bats may become immune for life after surviving an LBV infection.

Filoviruses

Filoviruses infamously include the genera Marburgvirus and Ebolavirus, both of which are believed to be maintained in bat reservoirs. Of the seven mechanistic models of bat-filovirus systems that we reviewed, only one (by Ekipa Fanihy!) was fitted to data. This study fitted an ‘MSIRN’ model to age-structured serological data collected from Madagascan flying foxes (Pteropus rufus). Here, the M stands for ‘Maternally-derived immunity’ – a process by which newborn bats receive antibodies from their mothers, and ‘N’ (non-antibody mediated immune) represents a class of individuals who maintained lifelong immunity not detectable by an antibody response. The model proposes an explanation for the age-structured serological data, hypothesizing that cell-mediated or innate immunity may play a role in bat filovirus maintenance. The low force of infection (or per capita rate at which individuals become infected) estimated for this flying fox population suggests that spatial metapopulation dynamics, in which infections blink in and out of local populations, may play a role in virus maintenance in this system.

Henipaviruses

Bats infected with henipaviruses shed virus in their urine. This allows researchers to noninvasively collect urine samples beneath roosts. Two of the three focal studies of this section modeled transmission of Ghanaian henipavirus (GhV) collected from E. helvum bats sampled from populations across Africa, and from a captive colony in Ghana. The third study, by Ekipa Fanihy, modeled an undescribed henipavirus identified serologically in the Madagascan fruit bat, Eidolon dupreanum. The pan-African and Malagasy studies came to similar conclusions, showing an important role for waning immunity in explaining patterns in the henipavirus data, though MSIRS model offered the best match to the GhV data while another MSIRN model recovered the Malagasy henipavirus data.

Coronaviruses

At the time of the writing of our paper, we found only one data-fitted model of a coronavirus system! The authors of this study found that an SIRS model that allows some bats to maintain a long (‘persistent’) infectious period best fit the transmission dynamics of an undescribed alphacoronavirus in the large-footed myotis bats (Myotis macropus) of Australia. Given our current situation, many more models of coronavirus dynamics in bat systems are likely to emerge in the upcoming years!