by Emily Ruhs

What if we could apply technology designed for human viral surveillance to other mammals known to host a variety of highly pathogenic viruses? In a recent paper published by the Brook lab in Frontiers in Public Health, we do just that!

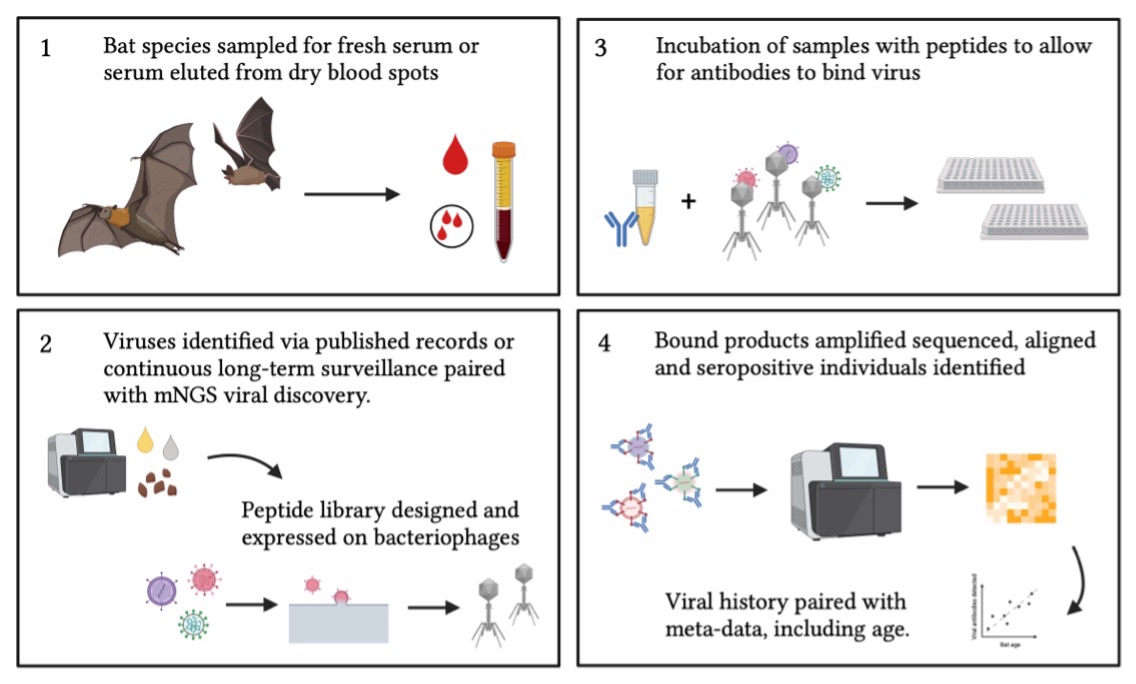

PhIP-Seq, or Phage-Immunoprecipitation Sequencing, uses recently advanced biomedical technology – broadly, multiplexed genomic sequencing - to identify antiviral antibody-specific binding to peptides displayed on bacteriophages. PhIP-Seq technology has previously been used to comprehensively profile human serum samples for antibodies to the VirScan peptidome, a peptide library representing over 200 viruses that constitute the complete known human virome (see here).

In this recent paper, we applied the original VirScan library to ~80 Pteropus alecto bats, collected from Queensland, Australia in 2015. P. alecto is a large, nectarivorous and frugivorous bat native to Australia, Papua New Guinea, and Indonesia. Pteropus alecto has been previously identified as a reservoir for zoonotic Australian bat lyssavirus (see here) and Hendra henipavirus (see here and here ). First, we asked whether this human-focused library could adequately profile antiviral antibodies to this bat host.

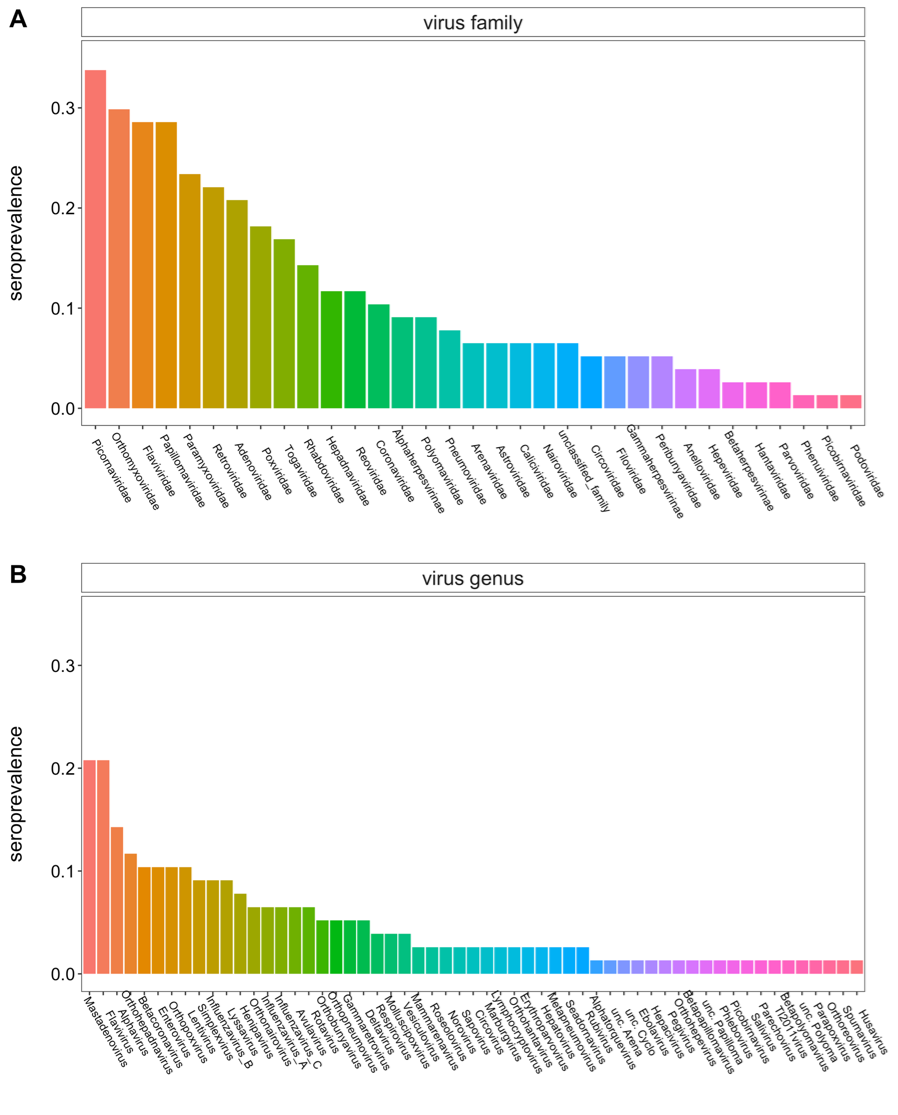

We identified preliminary evidence of prior viral exposure to 57 specific viral genera, 41 subfamilies, and 33 different families. These included putative evidence of prior exposure to multiple viral genera in P. alecto serum that represent the first record of association between these viruses and this bat host: alphatorquevirus, alphavirus, betapapillomavirus, betapolyomavirus, circovirus, deltavirus, erythroparvovirus, hepacivirus, hepatovirus, husavirus, lymphocryptovirus, mammarenavirus, metapneumovirus, mulluscipoxvirus, norovirus, orthohepadnavirus, orthohepevirus, orthopoxvirus, orthoneumovirus, parapoxvirus, parechovirus, pegivirus, phlebovirus, picobirnavirus, roseolovirus, rotavirus, rubivirus, salivirus, sapovirus, seadornavirus, spumavirus, and vesiculovirus. On average, P. alecto had a mean of 3.69 viral genera antibodies identified per individual – which compares to an average of 10 viral genera antibodies per human host (here). Particularly, this VirScan assay successfully differentiated between past exposures to the closely related bat virus genera, ebolavirus and marburgvirus, and even distinguished Hendra/Nipah virus exposure from other peptides within the bat-infecting henipavirus genus. However, we were sometimes unable to serologically distinguish exposures among subfamilies, likely in large part because certain viruses (e.g., picornaviruses) included in the VirScan library are entirely human in origin.

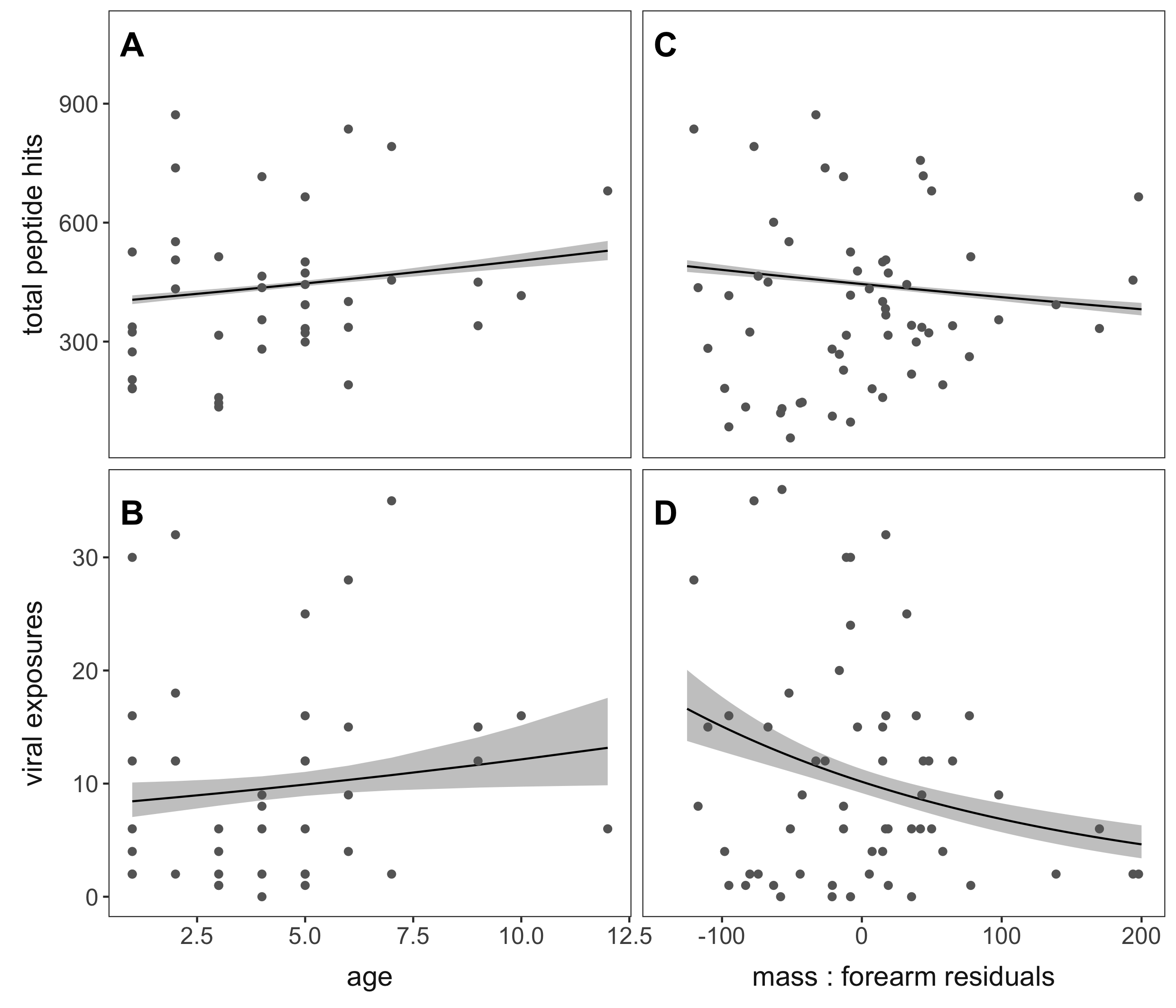

Our next objective was to understand how viral exposures covary with age and body condition in these P. alecto bats. Using records from age cementum analysis (for more information see here!) and mass : forearm residuals – essentially a body-mass index “BMI” for bats – we separated out the top viral genera and explored patterns across age and mass residuals.

We found that total peptide hits and the number of viral exposures slightly increased with age, which makes logical sense because as animals get older there are more opportunities to get exposed to new pathogens – more time being vulnerable! We also saw that the greater the number of viral exposures, the more likely P. alecto were to have low mass residuals, meaning that they were potentially in worse condition. These results suggest either some subtle negative effects of continued or repeated viral infection on bat health over time, or a heightened susceptibility to viral exposure in individuals with poor nutritional status – which is intriguing given that bats are thought to not suffer health consequences with viral infection.

As we are all aware, bats have recently been the focus of attention due to the COVID-19 pandemic and other implicated bat-hosted viruses; therefore, broad serological surveillance aimed at elucidating the viruses that bats host are of great public and scientific interest. VirScan offers a promising alternative for future wildlife surveillance efforts, combining the broad historical outlook of serology—by which to identify both current and past infections—with the broad, multi-pathogen approach of meta-genomic next generation sequencing. While we show here that the original VirScan library does a pretty good job at identifying antibodies to human-viruses in bats, future applications of this platform in bat systems should aim to develop a bat-focused peptide library, which can effectively distinguish between multiple exposures to closely-related bat viruses or bat virus strains in a single viral genus.

Currently, we are working on developing this bat-focused library in conjunction with the Grainger Bioinformatics Center at the Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago, Illinois). Keep a look out for new developments!