By Cara Brook

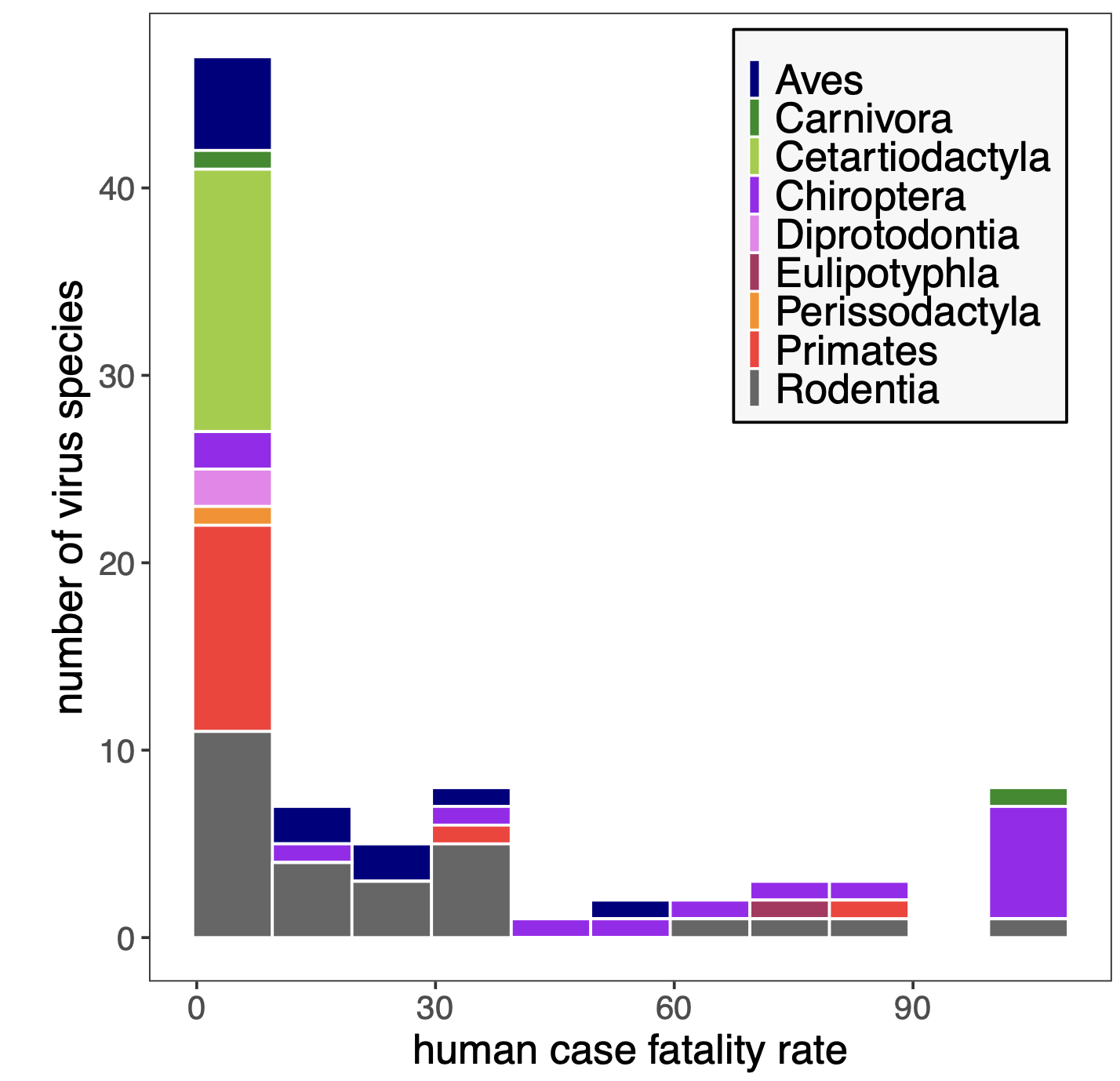

In a paper the Brook lab published in PNAS in 2022, we compiled data from the literature to demonstrate that bat-borne viral zoonoses result in higher case fatality rates following spillover to humans than do viruses derived from any other known mammal- or bird host. These highly virulent bat zoonoses include Ebola and Marbugh filoviruses, Hendra and Nipah henipaviruses, and SARS and MERS coronaviruses. In our new paper, out this week in PLoS Biology, we offer a mechanistic explanation for the extraordinary virulence of bat virus zoonoses.

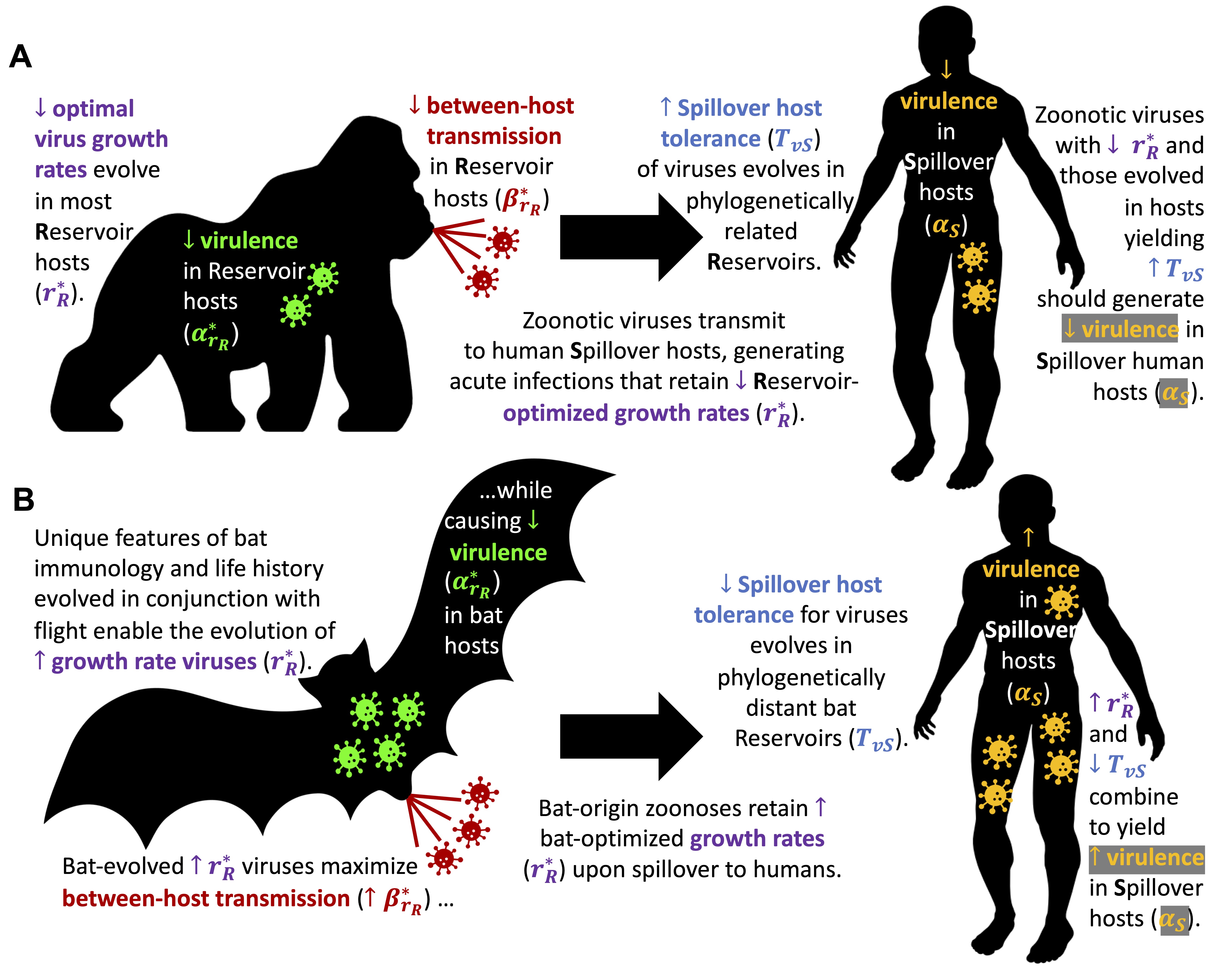

Our paper presents a theoretical model that seeks to mechanistically recapture the virulence of zoonotic viruses in two key steps: first allowing a virus to evolve over long timescales in its reservoir host, then second, to spillover on shorter timescales in a human host while still maintaining traits (specifically its growth rate) optimized on its original reservoir.

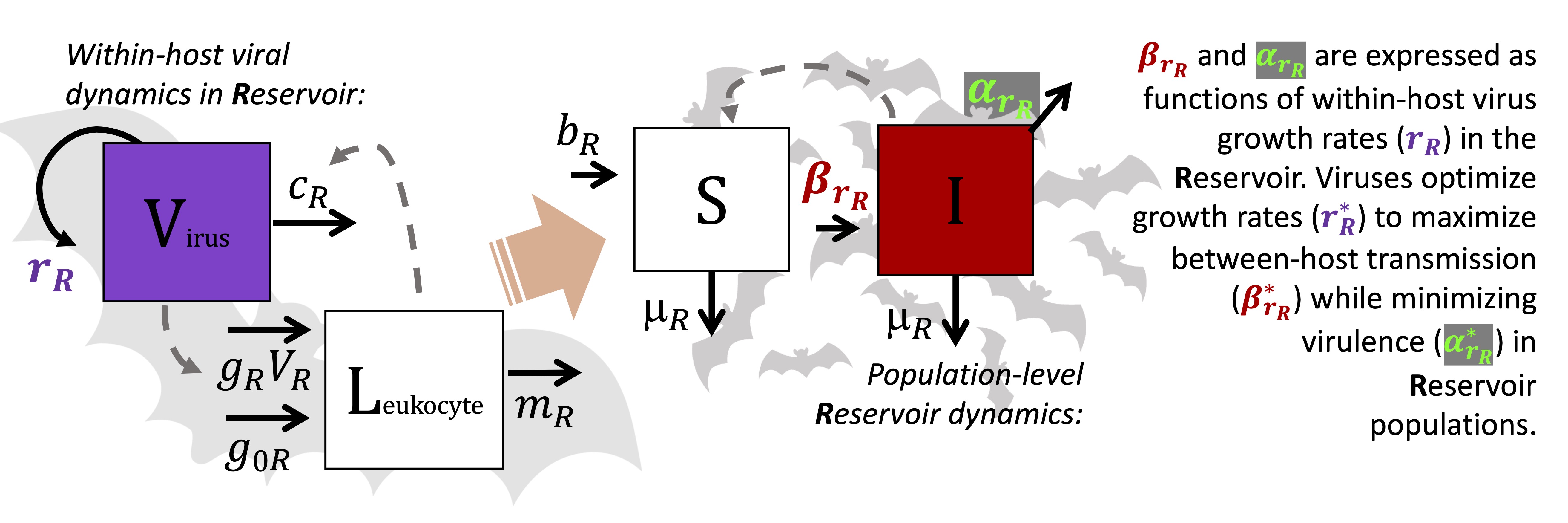

In our first analysis, we focus on virus adaption in the reservoir host, using a nested, within-host and population-level model and a technique known as ‘adaptive dynamics’ to derive a mathematical expression that demonstrates how a virus’s evolutionarily optimal growth rate–which we call r*–should reflect the diverse life history traits and physiologies of its reservoir. The optimal r* balances the benefits of enhanced between-host transmission and the costs of elevated virulence for the host that both result from higher virus growth rates. Faster-reproducing viruses generate higher virus densities in their hosts to facilitate transmission to new hosts–but these high virus densities can also cause direct pathology (disease) or elicit inflammatory immunopathological responses in their hosts. In disease ecology, this paradox is known as the ‘transmission-virulence tradeoff’.

Using life history data from the literature, we make predictions of the evolutionarily optimal virus growth rate (r*) for 19 different mammalian orders. These r* predictions vary across different mammal hosts because of variation in the extent to which higher r* enhances transmission or casuses virulence for diverse host physiologies. We predict the evolution of particularly high r* values for bat-evolved viruses as a result of a few unique features of bat physiology and immunity that minimize the pathology typically incurred by a high growth rate virus. In particular, several bat species are known to have perpetually primed antiviral immune systems (via constitutive expression of the antiviral cytokine, IFN-α), offering a resistance trait that elevates r* in our model. In addition, bats also appear to be highly resilient to the immunopathological consequences of virus control by the immune system (chiefly inflammation), providing yet another parameter value in our model (‘tolerance of immunopathology’) which drives r* predictions upwards. Critically, we scale this latter parameter as proportional to the residual of predicted lifepsan per body size, such that mammalian orders with longer lifespans than predicted for their body size have high values for the tolerance of immunopathology–and vice versa. As bats are the longest-lived mammals for their body size known, we model very high values for immunopathological tolerance in bats, thus elevating r*.

The link between inflammation, longevity, and tolerance of virus infection rests on a body of recent work out Dr. Linfa Wang’s lab at Duke National University of Singapore, which demonstrates how bat longevity results from unique molecular mechanisms that mitigate inflammation–which are thought to have first evolved to dispel the extreme physiological stress that accrues with the highly metabolic activity of powered flight, itself unique to bats among all mammals. See here, here, and here for some relevant examples.

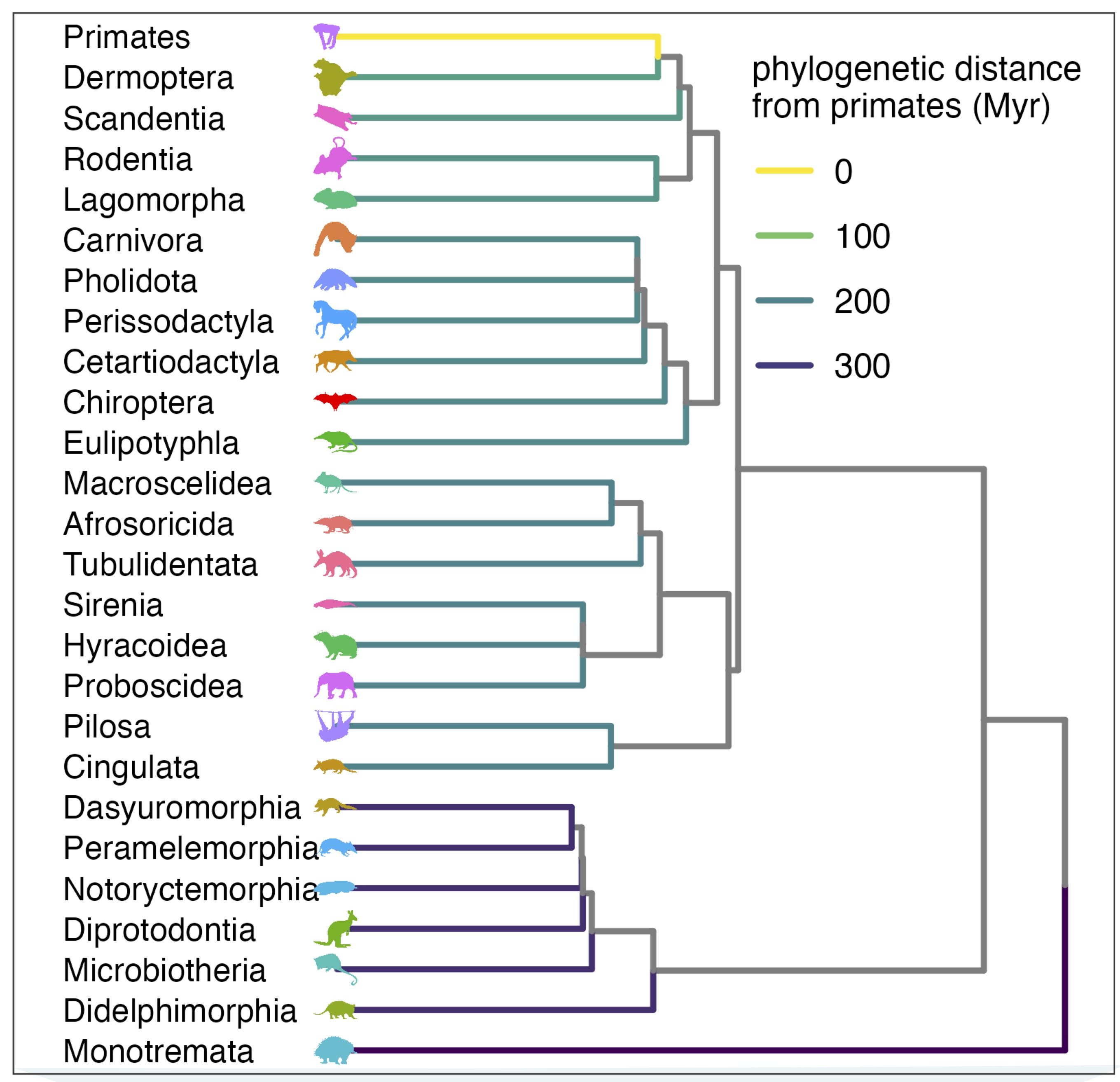

After evolving optimal virus growth rates for reservoir hosts, we next allow these reservoir-optimized viruses to “spillover” into secondary, human hosts. We assume that the first spillover infections in the human host should be acute, allowing limited opportunity for virus adaptation to the new host. Thus, we model human infections using immunological and physiological properties of the human host but with the same r* virus growth rate previously optimized on the reservoir host. We also include a term for the ‘tolerance of direct virus pathology’ in the human host which we model as proportional to phylogenetic distance between reservoir host and human. This term is meant to embody any mismatch in immunity and physiology between reservoir and human not already captured in the optimal virus growth rate–which may result in further virulence in the spillover host.

From this, we are able to make predictions of the variation in virulence–here, mortality–caused by zoonotic viruses evolved in diverse reservoir host orders following spillover to human hosts. In most cases, the predicted virulence in humans mirrors the predicted r* values, such that reservoir-optimized viruses with high r* also cause high virulence in humans. For a subset (8) of reservoir orders, including bats, we can compare their predicted relative virulence in humans (from our nested model) against that previously presented in our 2022 paper. Our model does quite well in this regard–most notably recapturing the extreme virulence of bat virus zoonoses.

Intriguingly, our model also allows us to make spillover virulence predictions for viruses derived from reservoir orders from which zoonoses have yet to be demonstrated. For example, we predict that viruses evolved in the order Monotremata (echnidna and platypus) should evolved high growth rates likely to cause virulence in the event that they spilled over to humans. Importantly, our paper does not consider the probability of this zoonosis occurring–and given the large phylogenetic distance between humans and monotremes–such an event would be highly unlikely to begin with. Before getting too excited about these virulence forecasts, it’s important to note that we make predictions only at the very coarse, crude level of mammalian order–and base these predictions on extremely limited within-host immunological and physiological data available for comparison across mammals. In reality, we should expect virulence to vary greatly based on species-level differences in the life history and physiological traits modeled here.

All told, our paper is, essentially, a robust, quantitative hypothesis meant to stimulate further data collection at the in vitro scale that will facilitate more fine-scaled predictions and empirical tests of those predictions in the future. In previous work in bat cell tissue culture, we found some evidence of high virus growth rates evolving in bat immune systems. In upcoming work, we plan to use similar approaches to directly challenge and evaluate the predictions outlined here.

For further insights, read this fantastic primer summarizing our paper by Samuel Alizon!